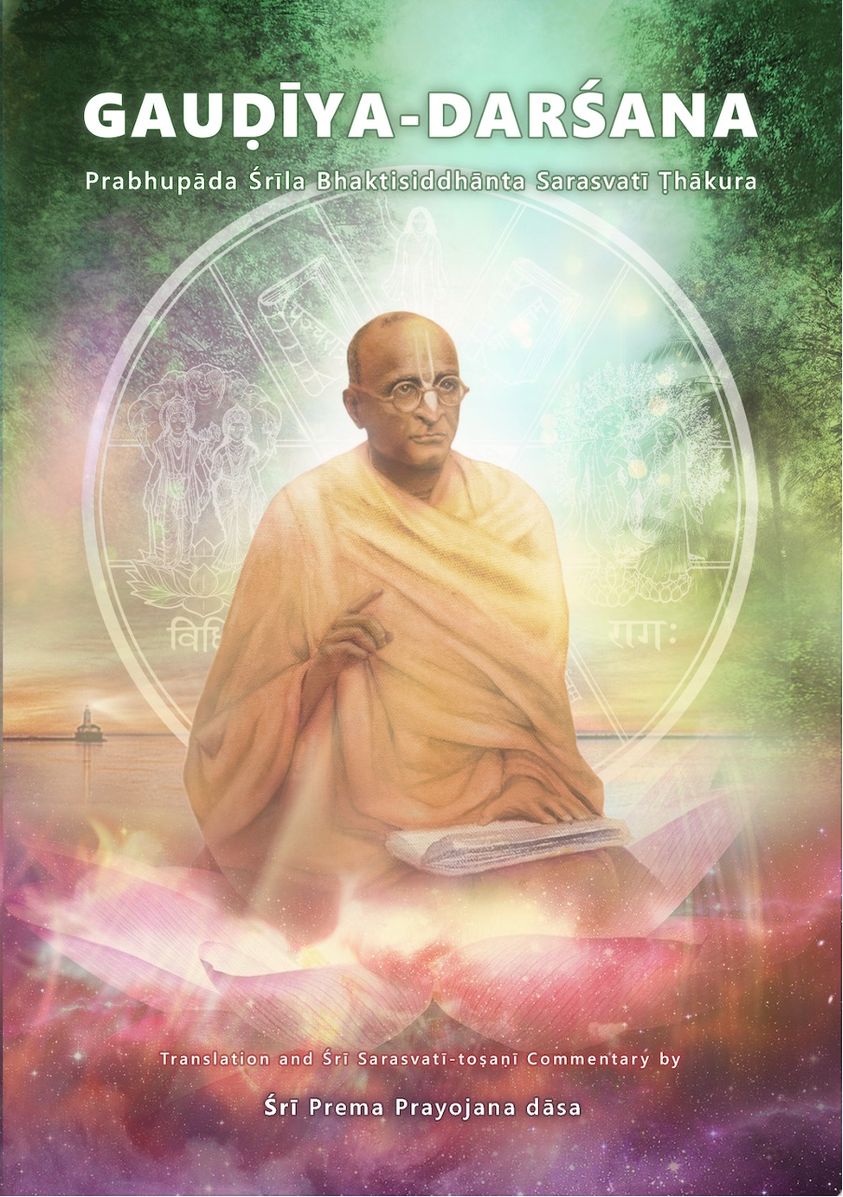

This is an excerpt from the book Bhakti-tattva-viveka, "Deliberation upon the true nature of devotion"

The divine couple Sri Sri Radha and Krishna

Composed by Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura and translated from the Hindi edition of the book by Śrī Śrīmad Bhaktivedānta Nārāyaṇa Mahārāja. Please also visit our Book Store at http://bhaktistore.com/

Chapter One The Intrinsic Nature of Bhakti

yugapad rājate yasmin

bhedābheda vicitratā

vande taṁ kṛṣṇa-caitanyaṁ

pañca-tattvānvitaṁ svataḥ

praṇamya gauracandrasya

sevakān śuddha-vaiṣṇavān

bhakti-tattva vivekā khyaṁ

śāstraṁ vakṣyāmi yatnataḥ

viśva-vaiṣṇava dāsasya

kṣudrasyākiñcanasya me

etasminn udyame hy ekaṁ

balaṁ bhāgavatī kṣamā

I offer obeisances unto Śrī Kṛṣṇa Caitanya, who is naturally manifest with His four primary associates in the pa—ca-tattva and in whom the contrasting qualities of unity (abheda) and distinction (bheda) simultaneously exist. After offering obeisances unto the servants of Śrī Gauracandra, who are all pure Vaiṣṇavas, I undertake with utmost care the writing of this book known as Bhakti-tattva-viveka. Being an insignificant and destitute servant of all the Vaiṣṇavas in the world (viśva-vaiṣṇava dāsa), in this endeavour of mine I appeal for their divine forgiveness, for that is my only strength. Most respectable Vaiṣṇavas, our sole objective is to relish and propagate the nectar of pure devotion (śuddha-bhakti) unto Lord Hari. Therefore our foremost duty is to understand the true nature of śuddha-bhakti.

Srila Bhaktivinodha Thakura

This understanding will benefit us in two ways. First, knowing the true nature of pure devotion will dispel our ignorance concerning the topic of bhakti and thus make our human lives successful by allowing us to relish the nectar derived from engaging in bhakti in its pure form. Secondly, it will enable us to protect ourselves from the polluted and mixed conceptions that currently exist in the name of pure devotion. Unfortunately, in present-day society, in the name of śuddha-bhakti various types of mixed devotion, such as karma-miśrā (mixed with fruitive action), jnana-miśrā (mixed with speculative knowledge) and yoga-miśrā (mixed with various types of yoga processes), as well as various polluted and imaginary conceptions, are spreading everywhere like germs of plague.

Srila Bhaktivedanta Narayana Maharaja

People in general consider these polluted and mixed conceptions to be bhakti, respect them as such, and thus remain deprived of unalloyed devotion. These polluted and mixed conceptions are our greatest enemies. Some people say that there is no value in bhakti, that God is an imaginary sentiment only, that man has merely created the image of a God in his imagination and that bhakti is just a diseased state of consciousness that cannot benefit us in any way. These types of people, though opposed to bhakti, cannot do much harm to us, because we can easily recognise them and avoid them. But those who propagate that devotion unto the Supreme Lord is the highest path yet behave against the principles of śuddha-bhakti and also instruct others against the principles of śuddha-bhakti can be especially harmful to us. In the name of bhakti they instruct us against the actual principles of devotional life and ultimately lead us onto a path that is totally opposed to bhagavad-bhakti. Therefore with great endeavor our preceptors have defined the intrinsic nature (svarūpa) of bhakti and have repeatedly cautioned us to keep ourselves away from polluted and mixed concepts. We shall deliberate on their instructions in sequence. They have compiled numerous literatures to establish the svarūpa of bhakti and, amongst them, Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu is the most beneficial. In defining the general characteristics of unalloyed devotion, Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī has written there (verse 1.1.11):

anyābhilāṣitā-śūnyaṁ

jñāna-karmādy anāvṛtam

ānukūlyena kṛṣṇānu-

śīlanaṁ bhaktir uttamā

The cultivation of activities that are meant exclusively for the pleasure of Śrī Kṛṣṇa, or in other words the uninterrupted flow of service to Śrī Kṛṣṇa, performed through all endeavors of the body, mind and speech, and through the expression of various spiritual sentiments (bhāvas), which is not covered by jñāna (knowledge aimed at impersonal liberation) and karma (reward-seeking activity), and which is devoid of all desires other than the aspiration to bring happiness to Śrī Kṛṣṇa, is called uttama-bhakti, pure devotional service. In the above verse, each and every word has to be analysed; otherwise we cannot understand the attributes of bhakti. In this verse, what is the meaning of the words uttama-bhakti? Do the words uttama-bhakti, meaning “topmost devotion”, also imply the existence of adhama-bhakti, inferior devotion? Or can they mean something else? Uttama-bhakti means the stage where the devotional creeper is in its completely pure or uncontaminated form. For example, uncontaminated water means pure water, meaning that in this water there is no color, smell or adulteration of any kind caused by the addition of another substance. Similarly the words uttama-bhakti refer to devotion that is devoid of any contamination, adulteration, or attachment to material possessions and that is performed in an exclusive manner.

Srila Rupa Gosvami

The usage of qualifying adjectives in this verse teaches us that we should not accept any sentiments that are opposed to bhakti. The negation of sentiments that are opposed to bhakti inevitably directs us towards the pure nature of bhakti itself. Perhaps by merely using the word bhakti alone this meaning is indicated, since the word bhakti already contains within it all these adjectives anyway. Then has Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī, the ācārya of the profound science of devotional mellows (bhakti-rasa), employed the qualifying adjective uttamā (topmost) for no reason? No – just as when desiring to drink water people generally ask, “Is this water uncontaminated?” – similarly, in order to describe the attributes of uttama-bhakti, our preceptors considered it necessary to indicate that people mostly practise miśra-bhakti, mixed devotion. In reality, Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī is aiming to describe the attributes of kevala-bhakti, exclusive devotion. Chala-bhakti (pretentious devotion), pratibimba-bhakti (a reflection of devotion), chāyā-bhakti (a shadow of devotion), karma-miśra-bhakti (devotion mixed with fruitive action), jnana-miśra-bhakti (devotion mixed with impersonal knowledge) and so on are not śuddha-bhakti. They will all be examined in sequence later on. What are the intrinsic attributes (svarūpa-lakṣaṇa) of bhakti?

To answer this question it is said that bhakti is anukūlyena kṛṣṇānuśīlana, the cultivation of activities that are meant exclusively for the pleasure of Śrī Kṛṣṇa. In his Durgama-saṅgamanī commentary on Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu, Śrīla Jīva Gosvāmī has explained that the word anuśīlanam has two meanings. First, it means cultivation through the endeavors to engage and disengage one’s body, mind and words. Secondly, it means cultivation towards the object of our affection (prīti) through mānasī-bhāva, the sentiments of the heart and mind. Although anuśīlana is of two types, the cultivation through mānasī-bhāva is included within cultivation by ceṣṭā, one’s activities. Hence, one’s activities or endeavours (ceṣṭā) and one’s internal sentiments (bhāva) are mutually interdependent, and in the end it is the ceṣṭā that are concluded to be the sole characteristic of cultivation. Only when the activities of one’s body, mind and words are favourably executed for the pleasure of Kṛṣṇa is it called bhakti. The demons Kaṁsa and Śiśupāla were always endeavoring towards Kṛṣṇa with body, mind and words but their endeavors will not be accepted as bhakti because such endeavours were unfavorable to Kṛṣṇa’s pleasure. Unfavourable endeavors cannot be called bhakti. The word bhakti is derived from the root verb form bhaj. It is said in the Garuḍa Purāṇa (Pūrva-khaṇḍa 231.3):

bhaj ity eṣa vai dhātuḥ

sevāyāṁ parikīrtitaḥ

tasmāt sevā budhaiḥ proktā

bhaktiḥ sādhana-bhūyasī

The verbal root bhaj means ìto render service. Therefore thoughtful sādhakas should engage in the service of Śrī Kṛṣṇa with great endeavor, for it is only by such service that bhakti is born. According to this verse, loving devotional service to Kṛṣṇa is called bhakti. Such service is the intrinsic attribute of bhakti. In the main verse from Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu (1.1.11), the word kṛṣṇānuśīlanam has been used. The purport of this is that Svayam Bhagavān Śrī Kṛṣṇa is the sole, ultimate objective indicated by the term kevala-bhakti (exclusive devotion). The word bhakti is also used for Nārāyaṇa and various other expansions of Kṛṣṇa, but the complete sentiments of bhakti that can be reciprocated with Kṛṣṇa cannot be reciprocated with other forms. This point can be analysed in detail on another occasion when the topic is more suitable for it. For the time being it is necessary to understand that the Supreme Lord in His Bhagavān feature is the only object of bhakti. Although the supreme absolute truth (para-tattva) is one, it is manifested in three forms; that is, Brahman, Paramātmā and Bhagavān. Those who try to perceive the absolute truth through the cultivation of knowledge (jnana) cannot realize anything beyond Brahman.

Through such spiritual endeavor they try to cross material existence by negation of the qualities of the material world (a process known as neti-neti); thus they imagine Brahman to be inconceivable, unmanifest, formless and immutable. But merely imagining the absence of material qualities does not grant one factual realisation of the absolute truth. Such spiritualists think that because the names, forms, qualities and activities in the material world are all temporary and painful, Brahman – which exists beyond the contamination of matter – cannot possess eternal names, form, qualities, pastimes and so on. They argue on the basis of evidence from the Śrutis, which emphasize the absence of material attributes in the Supreme, that the absolute truth is beyond the purview of mind and words, and that it has no ears, limbs or other bodily parts. These arguments have some place, but they can be settled by analyzing the statement of Advaita Ācārya found in the Śrī Caitanya-candrodaya-nāṭaka (6.67) written by Kavi Karṇapūra:

yā yā śrutir jalpati nirviśeṣaṁ

sā sāvidhatte saviśeṣam eva

vicāra-yoge sati hanta tāsāṁ

prāyo balīyaḥ saviśeṣam eva

In whatever statements from the Śrutis where the impersonal aspect of the absolute truth is indicated, in the very same statements the personal aspect is also mentioned. By carefully analyzing all the statements from the Śrutis as a whole, we can see that the personal aspect is emphasized more. For example, one Śruti says that the absolute truth has no hands, no legs and no eyes, but we understand that He does everything, travels everywhere and sees everything. The pure understanding of this statement is that He doesn’t have material hands, legs, eyes and so on as conditioned souls do. His form is transcendental, meaning that it is beyond the twenty-four elements of material nature and purely spiritual. By the cultivation of jnana it will appear that impersonal Brahman is the supreme truth. Here the subtlety is that jnana itself is material, meaning in the material world whatever knowledge we acquire or whatever philosophical principle (siddhānta) we establish is done by depending solely upon material attributes. Therefore, either that principle is material or by applying the process of negation of the material (vyatireka) we conceive of a principle that is the opposite of gross matter, but by this method one cannot achieve the factual supreme truth.

Śrīla Jīva Gosvāmī

In his Bhakti-sandarbha Śrīla Jīva Gosvāmī has outlined the relative truth that is attained by those who pursue the path of impersonal knowledge as follows:

prathamataḥ śrotṛṇām hi vivekas tāvān eva, yāvatā jaḍātiriktaṁ cin-mātraṁ vastūpasthitaṁ bhavati. tasmiṁś cin-mātre ípi vastūni ye viśeṣāḥ svarūpa-bhūta-śakti-siddhāḥ bhagavattādi-rūpā varttante tāṁs te vivektuṁ na kṣamante. yathā rajanī-khaṇḍini jyotiṣi jyotir mātratve ípi ye maṇḍalāntar bahiś ca diva-vimānādi-paraspara-pṛthag-bhūta-raśmi-paramāṇu-rūpā viśeṣās tāṁś carma-cakṣuṣa na kṣamanta ity anvayaḥ tadvat. pūrvavac ca yadi mahat-kṛpā-viśeṣeṇa divya-dṛṣṭitā bhavati tadā viśeṣopalabdhiś ca bhavet na ca nirviśeṣa-cin-mātra-brahmānubhavena tal-līna eva bhavati. (214) idam eva (Bhagavad-gītā (8.3) ìsvabhāvo ídhyātmam ucyateî ity anena śrī-gītāsūktam. svasya śuddhasyātmano bhāvo bhāvanā ātmany adhikṛtya vartamānatvād adhyātma-śabdenocyate ity arthaḥ.

In the beginning the students who are pursuing the path of jñāna require sufficient discrimination to comprehend the existence of a transcendent entity (cinmaya-vastu) that is beyond the contamination of gross matter. Although the specific attributes of Godhead established by the potencies inherent within the Lordís very nature are intrinsically present within that transcendent entity, the adherents of the path of jñāna are unable to perceive them. For example, the sun is a luminary that dispels the darkness of night. Although its luminous quality is easily understood, the inner and outer workings of the sun planet, the difference that exists between individual particles of light, and the specific distinguishing features of the innumerable atomic particles of light are all imperceptible to human eyes. Similarly, those who view the transcendent entity through the eyes of impersonal knowledge are unable to perceive the Lordís divine personal attributes. If, as previously described, one acquires transcendental vision by the special mercy of great devotees, one will be able to directly recognise the Lordís personal attributes. Otherwise, by realisation of the impersonal existential Brahman, one will attain only the state of merging into that Brahman.

This knowledge is stated in Bhagavad-gītā (8.3): ìsvabhāvo ídhyātmam ucyate — the inherent nature of the living entity is known as the self. The meanings of the words svabhāva and adhyātma are as follows. Sva refers to the pure self (śuddha-ātmā), and the word bhāva refers to ascertainment. Hence the ascertainment of the pure living entity as a unique individual, eternally related to the Supreme, is known as svabhāva. When the self (ātmā) is made the principal subject of focus and thus given the power to act in its proper function, it is known as adhyātma. (Anuccheda 216) The purport of this is that when spiritual knowledge is acquired through the process of negation (neti-neti), the absolute truth, which is transcendental to the illusory material potency (māyā), is realised only partially. The variegated aspect of transcendence, which lies much deeper within, is not realised. If one who follows this process meets a personalist, self-realised Vaiṣṇava spiritual master, then only can he be protected from the impediment (anartha) of impersonalism. Those who pursue the path of yoga in the end arrive only at realisation of the all-pervading Supersoul, Paramātma. They cannot attain realisation of the Supreme Lord in His ultimate manifestation. Paramātmā, Iśvara, personal Viṣṇu and so on are the objects of research in the yoga process.

In this process we can find a few attributes of bhakti, but it is not unalloyed devotion. Generally, religious principles in this world that pass for the topmost spiritual path are all merely yoga processes that strive for realisation of the Paramātmā feature. We cannot expect that in the end all of them will ultimately lead us to the topmost path (bhāgavata-dharma), because in the process of meditation there are numerous obstacles before one finally realises the absolute truth. Besides, when after practising either yoga or meditation for some time one imagines that “I am Brahman”, there is the maximum possibility of falling into the trap of impersonal spiritual jnana. In this process, realisation of the eternal form of Bhagavān and the variegated characteristics of transcendence is not available. The form that is imagined at the time of meditational worship (upāsanā) – whether it be the gigantic form of the Lord conceived in the shape of the universe or the four-armed form situated within the heart – is not eternal. This process is called paramātma-darśana, realisation of the Supersoul. Although this process is superior to the cultivation of impersonal jnana, it is not the perfect and all-pleasing process. Aṣṭāṅga-yoga, haṭha-yoga, karma-yoga and all other yoga practices are included within this process. Although rāja- or adhyātma-yoga follows this process to a certain extent, in most cases it is merely included within the process of jnana. The philosophical conclusion is that realisation of the Supersoul cannot be called śuddha-bhakti. In this regard it is said in Bhakti-sandarbha: “antaryāmitvamaya-māyā-śakti-pracura-cic-chakty āśā-viśiṣtaṁ paramātmeti – after the creation of this universe, the expansion of the Supreme Lord who enters it as the controller of material nature and who is situated as the maintainer of the creation is known as Jagadīśvara, the all-pervading Paramātmā.”

His function is related more to displaying the external potency rather than the internal potency. Therefore this aspect of the absolute truth is naturally inferior to the supreme and eternal Bhagavān aspect. Absolute truth realised exclusively through the process of bhakti is called Bhagavān. In Bhakti-sandarbha the characteristics of Bhagavān are described: “pari-pūrṇa-sarva-śakti-viśiṣṭa-bhagavān iti – the complete absolute truth endowed with all transcendental potencies is called Bhagavān.” After the creation of the universe, Bhagavān enters it through His partial expansion as Paramātmā: as Garbhodakaśāyī, He is situated as the Supersoul of the complete universe, and as Kṣīrodakaśāyī, He is situated as the Supersoul in the hearts of the living entities. Again, in direct distinction from the manifested material worlds, Bhagavān appears as the impersonal Brahman. Hence, Bhagavān is the original aspect of Godhead and the supreme absolute truth. His intrinsic form (svarūpa-vigraha) is transcendental. Complete spiritual bliss resides in Him. His potencies are inconceivable and beyond any reasoning. He cannot be fathomed by any process fabricated by the knowledge of the infinitesimal living entity (jīva). By the influence of His inconceivable potency, the entire universe and all the living entities residing within it have manifested.

Jīvas manifesting from the marginal potency (taṭastha-śakti) of Bhagavān become successful only by following the path of engaging exclusively in His loving transcendental service. Then by the practice of chanting the holy name (nāma-bhajana), one can realise through one’s transcendental eyes the unparalleled beauty of Bhagavān. The processes of jnana and yoga are incapable of approaching Bhagavān. When approached through the cultivation of impersonal knowledge, the Lord appears as the formless and effulgent impersonal Brahman, and if He is seen through the yoga process, He appears as Paramātmā invested within this material creation. Bhakti is supremely pure. It is very painful for Bhakti-devī, the personification of bhakti, to see the Supreme Personality in His lesser manifestations. If she sees this anywhere, she cannot tolerate it. Out of these three manifestations of the absolute truth, it is only the manifestation of Bhagavān’s personal form that is the object of bhakti. But even within Bhagavān’s personal manifestation there is one important distinction. Where the internal potency (svarūpa-śakti) displays its complete opulence (aiśvarya), there Bhagavān appears as Vaikuṇṭhanātha Nārāyaṇa, and where the internal potency displays its supreme sweetness (mādhurya), there Bhagavān appears as Śrī Kṛṣṇa.

Despite being predominant almost everywhere, aiśvarya loses its charm in the presence of mādhurya. In the material world we cannot draw such a comparison; no such example is visible anywhere. In the material world aiśvarya is more influential than mādhurya, but in the spiritual world it is completely the opposite. There mādhurya is superior and more influential than aiśvarya. O my dear devotees, all of you just deliberate upon aiśvarya one time, and then afterwards lovingly bring sentiments of mādhurya into your hearts. By doing so you will be able to understand this truth. Just as in the material world when the sun rises and consumes the moonlight, similarly when a taste of the sweetness of mādhurya appears in a devotee’s heart, he no longer finds aiśvarya to be tasteful. Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī has written (Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu (1.2.59)):

siddhāntatas tv abhede ípi

śrīśa-kṛṣṇa-svarūpayoḥ

rasenotkṛṣyate kṛṣṇa-

rūpam eṣā rasa-sthitiḥ

Although from the existential viewpoint Nārāyaṇa and Kṛṣṇa are non-different, Kṛṣṇa is superior due to possessing more rasa. Such is the glory of rasa-tattva. This topic will be made clear later in this discussion. But for now it is essential to understand that the favourable cultivation of activities meant to please Śrī Kṛṣṇa (ānukūlyena anuśīlanam) is the sole intrinsic characteristic (svarūpa-lakṣaṇa) of bhakti. Thus this confirms the same statement made in the verse under discussion from Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu (1.1.11). To remain devoid of desires separate from the desire to please Śrī Kṛṣṇa (anyābhilāṣitā) and free from the coverings of jnanaand karma (jnana-karmādy anāvṛtam) are the marginal characteristics (taṭastha-lakṣaṇa) of bhakti. Viṣṇu-bhakti pravakṣyāmi yayā sarvam avāpyate – in this half verse from Bhakti-sandarbha the marginal characteristics of bhakti are reviewed. Its meaning is that by the practice of the aforementioned viṣṇu-bhakti the living entity can attain everything. The desire to attain something is called abhilāṣitā. From the word abhilāṣitā one should not derive the meaning that the desire to progress in bhakti and to ultimately reach its perfectional stage is also to be rejected. “Through my practice of sādhana-bhakti I will one day attain the elevated stage of bhāva” – it is highly commendable for a devotee to maintain such a desire, but apart from this desire all other types of desire are fit to be rejected. There are two types of separate desire: the desire for sense gratification (bhukti) and the desire for liberation (mukti). Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī says (Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu (1.2.22)):

bhukti-mukti-spṛhā yāvat

piśācī hṛdi vartate

tāvad bhakti-sukhasyātra

katham abhyudayo bhavet

As long as the two witches of the desires for bhukti and mukti remain in a devotee’s heart, not even a fraction of the pure happiness derived from svarūpa-siddha-bhakti1 will arise. Both bodily and mental enjoyment are considered bhukti. To make an extraneous effort to remain free from disease or to desire palatable foodstuffs, strength and power, wealth, followers, wife, children, fame and victory, are all considered bhukti. To desire to take one’s next birth in a brāhmaṇa family or in a royal family, to attain residence in the heavenly planets or in Brahmaloka or to obtain any other type of happiness in one’s next life is also considered bhukti. Practice of the eightfold yoga system and to desire the eight or eighteen varieties of mystic perfections are also categorised as bhukti. The greed for bhukti forces the living entity to become subordinate to the six enemies headed by lust and anger. Envy easily takes over the heart of the living entity and rules it. Hence, to attain unalloyed devotion one has to remain completely aloof from the desire for bhukti. To abandon the desire for bhukti, a conditioned soul need not reject the objects of the senses by going to reside in the forest. Merely going to reside in the forest or accepting the dress of a renunciant (sannyāsī) will not free one from the desire for bhukti. If bhakti resides in a devotee’s heart, then even while living amidst the objects of the senses he will be able to remain detached from them and will be capable of abandoning the desire for bhukti. Therefore Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī says (Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu (1.2.254–6)):

rucim udvahatas tatra

janasya bhajane hareḥ

viṣayeṣu gariṣṭho ípi

rāgaḥ prāyo vilīyate

anāsaktasya viṣayān

yathārham upayuñjataḥ

nirbandhaḥ kṛṣṇa-sambandhe

yuktaṁ vairāgyam ucyate

prāpañcikatayā buddhyā

hari-sambandhi-vastunaḥ

mumukṣubhiḥ parityāgo

vairāgyaṁ phalgu kathyate

When the living entity develops a taste for kṛṣṇa-bhajana, at that time his excessive attachment for the objects of the senses starts gradually fading. Then with a spirit of detachment he accepts the objects of the senses only according to his needs, knowing those objects to be related to Kṛṣṇa and behaving accordingly. This is called yukta-vairāgya. The renunciation of those who, desiring liberation from matter, reject the objects of the senses considering them to be illusory is called phalgu, useless. It is not possible for an embodied soul to completely renounce the objects of the senses, but changing the enjoying tendency towards them while maintaining an understanding of their relation to Kṛṣṇa cannot be called sense gratification. Form (rūpa), taste (rasa), smell (gandha), touch (sparśa) and sound (śabda) are the objects of the senses. We should try to perceive the world in such a way that everything appears related to Kṛṣṇa, meaning that we should see all living entities as servants and maidservants of Kṛṣṇa. See gardens and rivers as pleasurable sporting places for Kṛṣṇa. See that all types of eatables are to be used as an offering for His pleasure. In all types of aromas, perceive the aroma of kṛṣṇa-prasāda. In the same way, see that all types of flavors are to be relished by Kṛṣṇa, see that all the elements we touch are related to Kṛṣṇa, and hear only narrations describing the activities of Kṛṣṇa or His great devotees. When a devotee develops such an outlook, then he will no longer see the objects of the senses as being separate from Bhagavān Himself. The tendency to enjoy the happiness obtained from sense gratification intensifies the desire for bhukti within the heart of a devotee and ultimately deviates him from the path of bhakti. On the other hand, by accepting all the objects of this world as instruments to be employed in Kṛṣṇa’s service, the desire for bhukti is completely eradicated from the heart, thus allowing unalloyed devotion to manifest there. As it is imperative to abandon the desire for bhukti, it is equally important to abandon the desire for mukti (liberation). There are some very deep principles and conceptions regarding mukti.

Five types of mukti are mentioned in the scriptures:

sālokya-sārṣṭi-sāmīpya-

sārūpyaikatvam apy uta

dīyamānaṁ na gṛhṇanti

vinā mat-sevanaṁ janāḥ

Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam (3.29.13) [Śrī Kapiladeva said:]

O my dear mother, despite being offered the five types of liberation known as sālokya, sārṣṭi, sāmīpya, sārūpya and ekatva, my pure devotees do not accept them. They only accept my transcendental loving service. Through sālokya-mukti one attains residence in the abode of Bhagavān. To obtain opulence equal to that of Bhagavān is called sārṣṭi-mukti. To attain a position in proximity to Bhagavān is called sāmīpya-mukti. To obtain a four-armed form like that of Bhagavān Viṣṇu is called sārūpya-mukti. To attain sāyujya-mukti (merging) is called ekatva. This sāyujya-mukti is of two kinds: brahma-sāyujya and īśvara-sāyujya. The cultivation of brahma-jnāna, impersonal knowledge, leads one to brahma-sāyujya, merging into the Lord’s effulgence. Also, by following the method prescribed in the scriptures that deal with self-realisation, one attains brahma-sāyujya. By properly observing the Pāta—jali yoga system, one attains the liberation known as īśvara-sāyujya, merging into the Lord’s form. For devotees both types of sāyujya-mukti are worthy of rejection. Those who desire to attain sāyujya as the perfectional stage may also follow the process of bhakti, but their devotion is temporary and fraudulent. They don’t accept bhakti as an eternal occupation and merely consider it to be a means to attain Brahman. Their conception is that after attaining Brahman, bhakti does not exist. Therefore the bhakti of a sincere devotee deteriorates in the association of such spiritualists. Unalloyed devotion never resides in the hearts of those who consider sāyujya-mukti to be the ultimate perfection. Regarding the other types of liberation, Śrīla Rūpa Gosvāmī explains (Bhakti-rasāmṛta-sindhu (1.2.55–7)):

atra tyājyatayaivoktā

muktiḥ pañca-vidhāpi cet

sālokyādis tathāpy atra

bhaktyā nāti virudhyate

sukhaiśvaryottarā seyaṁ

prema-sevottarety api

sālokyādir-dvidhā tatra

nādyā sevā-juṣāṁ matā

kintu premaika-mādhurya

juṣa ekāntino harau

naivāṅgī kurvate jātu

muktiṁ pañca-vidhām api

Although the aforementioned five types of liberation are worthy of rejection by devotees, the four types of sālokya, sāmīpya, sārūpya and sārṣṭi are not completely adverse to bhakti. According to the difference in a particular devotee’s eligibility to receive them, these four types of liberation assume two forms: sva-sukha-aiśvarya-pradānakārī (that which bestows transcendental happiness and opulence) and prema-sevā-pradānakārī (that which bestows loving transcendental service unto Bhagavān). Those who reach the Vaikuṇṭha planets through these four types of liberation obtain the fruit of transcendental happiness and opulence. Servitors of the Lord never accept such liberation under any circumstance, and the loving devotees (premi-bhaktas) never accept any one of the five varieties of mukti. Therefore within pure unalloyed devotees the desire for liberation does not exist. Thus to remain free from the desires for liberation and sense gratification is anyābhilāṣitā-śūnya, being devoid of any desire other than that to please Śrī Kṛṣṇa. This is one of the marginal characteristics (taṭastha-lakṣaṇa) of bhakti. To remain uncovered by tendencies such as those for jnana(the cultivation of knowledge aimed at impersonal liberation) and karma (fruitive activity) is another marginal characteristic of bhakti. In the phrase jnana-karmādi, the word ādi, meaning “and so forth”, refers to the practice of mystic yoga, dry renunciation, the process of enumeration (sāṅkhya-yoga), and the occupational duties corresponding to one’s caste or creed. It has already been mentioned that the favourable cultivation of activities to please Śrī Kṛṣṇa is called bhakti.

The living entity is transcendental, Kṛṣṇa is transcendental, and bhakti-vṛtti – the tendency of pure devotion through which the living entity establishes an eternal relationship with Kṛṣṇa – is also transcendental. When the living entity is situated in his pure state, only then does the intrinsic attribute (svarūpa-lakṣaṇa) of bhakti act. At that time there is no opportunity for the marginal characteristics of bhakti to act. When the living entity is conditioned and situated in the material world, along with his constitutional identity (svarūpa) two more marginal identities are present: the gross and subtle bodies. Through the medium of these the living entity endeavours to fulfil his various desires while residing in the material world. Therefore, when introducing someone to the conception of unalloyed devotion, we have to acquaint him with the concept of anyābhilāṣitā-śūnya, being devoid of any desire other than the desire to please Śrī Kṛṣṇa. In the transcendental world this type of identification is not required. After becoming entangled in the ocean of material existence, the living entity becomes absorbed in various types of external activities and is thereby attacked by a disease called “forgetfulness of Kṛṣṇa”. Within the jīva suffering from the severe miseries caused by this disease arises a desire to be delivered from the ocean of material nescience. At that time within his mind he condemns himself, thinking, “Alas! How unfortunate I am! Having fallen into this insurmountable ocean of material existence, I am being thrown here and there by the violent waves of my wicked desires. At different times I am being attacked by the crocodiles of lust, anger and so forth.

I cry helplessly at my miserable condition but I don’t see any hope for my survival. What should I do? Do I not have any well-wisher? Is there any possible way I can be rescued? Alas! What to do? How will I be delivered? I don’t see any solution to my dilemma. Alas! Alas! I am most unfortunate.” In such a distressed state of helplessness, the living entity becomes exhausted and falls silent. Seeing the jīva in this condition, the most compassionate Śrī Kṛṣṇa then mercifully implants the seed of the creeper of devotion (bhakti-latā-bīja) within his heart. This seed is known as śraddhā, faith, and it contains within it the undeveloped manifestation of bhāva, the first sprout of divine love for Bhagavān. Nourished by the water of the cultivation of devotional activities headed by hearing and chanting, that seedling first sprouts, then grows leaves, and then finally flowers as it assumes the full form of a creeper. When in the end good fortune dawns upon the living entity, the creeper of devotion bears the fruit of prema, divine love. Now I will explain the gradual development of bhakti, starting from its seed-form of śraddhā. It is to be understood clearly that as soon as the seed of faith is sown in the heart, immediately Bhakti-devī appears there. Bhakti at the stage of śraddhā is very delicate like a new-born baby girl. From the very time of her appearance in a devotee’s heart she has to be very carefully kept in a healthy condition. Just as a householder protects his very tender baby daughter from sun, cold, harmful creatures, hunger and thirst, similarly the infant-like Śraddhā-devī must be protected from all varieties of inauspiciousness.

Otherwise the undesirable association of impersonal knowledge, fruitive activity, mystic yoga, attachment to material objects, dry renunciation and so forth will not allow her to gradually blossom into uttama-bhakti and will instead make her grow into a different form. In other words, faith will not eventually develop into bhakti but will merely assume the form of anarthas, impediments to pure devotion. The danger of disease remains until the tender Śraddhā-devī becomes free from the influence of anarthas and transforms into niṣṭhā, resolute determination. This occurs from being nurtured by the affectionate mother of the association of genuine devotees and from taking the medicine of bhajana. Once she has reached the stage of niṣṭhā, no anartha whatsoever can easily harm her. If Śraddhā-devī is not properly nurtured with the utmost care, she will be polluted by the germs, termites, mosquitoes and unhealthy environment of jnana-yoga (the cultivation of knowledge), vairāgya (dry renunciation), sāṅkhya-yoga (the process of enumeration) and so forth. In the conditioned stage, the pursuit of knowledge, renunciation and so on are unavoidable for the living entity, but if knowledge is of a particular variety that is unfavourable to devotion, it can ruin bhakti. Hence, according to Śrīla Jīva Gosvāmī the word jnanahere refers to the pursuit of impersonal Brahman. Jnanais of two types: spiritual knowledge that is directed towards obtaining mukti, and bhagavat-tattva-jnana, which arises simultaneously along with bhakti within the heart of the living entity. The first type of jnanais directly opposed to bhakti and it is essential to stay far away from it. Some people say that bhakti arises only after the cultivation of such spiritual knowledge, but this statement is completely erroneous. Bhakti actually dries up by the cultivation of such knowledge. On the other hand, knowledge concerning the mutual relationship (sambandha) between the Supreme Lord, the living entity and the illusory energy, which arises within the heart of the living entity through the faithful cultivation of devotional activities, is helpful for bhakti. This knowledge is called ahaituka-jnana, knowledge that is devoid of ulterior motive. Sūta Gosvāmī says in Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam (1.2.7):

vāsudeve bhagavati

bhakti-yogaḥ prayojitaḥ

janayaty āśu vairāgyaṁ

jñānaṁ ca yad ahaitukam

Bhakti-yoga that is performed for the satisfaction of the Supreme Lord Vāsudeva brings about detachment from all things unrelated to Him and gives rise to pure knowledge that is free from any motive for liberation and directed exclusively towards the attainment of Him. Now, by carefully reviewing all the previous statements, we can understand that to remain uncovered by jnana, karma and so forth – which means accepting them as subservient entities – and to engage in the favourable cultivation of activities meant to please Śrī Kṛṣṇa that are devoid of any other desire, is called uttama-bhakti. Bhakti is the only means by which the living entity can obtain transcendental bliss. Besides bhakti, all other methods are external. With the assistance of bhakti, sometimes fruitive activity (karma) is identified as āropa-siddha-bhakti, endeavours that are indirectly attributed with the quality of devotion, and sometimes the cultivation of impersonal knowledge (jnana) is identified as saṅga-siddha-bhakti, endeavours associated with or favourable to the cultivation of devotion. But they can never be accepted as svarūpa-siddha-bhakti, devotion in its constitutionally perfected stage. Svarūpa-siddha-bhakti is kaitava-śūnya, free from any deceit and full of unalloyed bliss by nature, meaning that it is devoid of any desire for heavenly enjoyment or the attainment of liberation. But in āropa-siddha-bhakti the desires for sense gratification (bhukti) and liberation (mukti) remain in a hidden position. Therefore it is also called sakaitava-bhakti, deceitful devotion.

O my dear intimate Vaiṣṇavas, by your constitutional nature you are attracted to svarūpa-siddha-bhakti and have no taste for āropa-siddha-bhakti or saṅga-siddha-bhakti. Although these two types of devotion are not actually bhakti by their constitution, some people refer to these two types of activities as bhakti. In fact they are not bhakti, but bhakti-ābhāsa, the semblance of real devotion. If by some good fortune through the practice of bhakti-ābhāsa one develops faith in the true nature of bhakti, then only can such practice transform into unalloyed devotion. But this does not happen easily, because by the practice of bhakti-ābhāsa there exists every possibility of remaining bereft of unalloyed devotion. Therefore, in all the scriptures, the instruction is to follow svarūpa-siddha-bhakti. In this short article, the intrinsic nature of unalloyed devotion has been explained. Having carefully reviewed all the instructions of our predecessor ācāryas, in summary form we are presenting their heartfelt sentiments in the following verse:

pūrṇa-cid-ātmake kṛṣṇe

jīvasyāṇu-cid-ātmanaḥ

upādhi-rahitā ceṣṭā

bhaktiḥ svābhāvikī matā

Śrī Kṛṣṇa is the complete, all-pervading consciousness who always possesses all potencies, and the jīva is the infinitesimal conscious entity who is likened to a single particle of light situated within a ray of the unlimited spiritual sun. The natural and unadulterated endeavour of the infinitesimal conscious entity towards the complete consciousness is called bhakti. The living entity’s persistence towards anyābhilāṣa (acting to fulfil desires other than the desire to please Śrī Kṛṣṇa), jnana(the cultivation of knowledge aimed at impersonal liberation) and karma (fruitive activity) is called “acquiring material designation”. We should understand that the natural inherent endeavour of the jīva can only mean the favourable cultivation of activities to please Śrī Kṛṣṇa.

Posted in

Posted in