Big questions about the big bang

When examined closely, the cosmologists’ confident explanation of the origin and structure of the universe falls apart

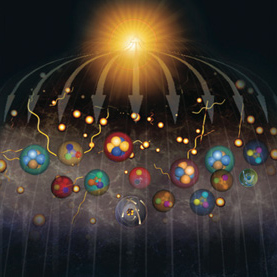

Look up at the night sky, full of stars and planets. Where did it all come from? These days most scientists will answer that question with some version of the big bang theory. In the beginning, you’ll hear, all matter in the universe was concentrated into a single point at an extremely high temperature, and then it exploded with tremendous force. From an expanding superheated cloud of subatomic particles, atoms gradually formed, then stars, galaxies, planets, and finally life. This litany has now assumed the status of revealed truth. In accounts that deliberately evoke the atmosphere of Genesis, the tale of primal origins is elaborately presented in countless textbooks, paperback popularizations, slick science magazines, and television specials complete with computer-generated effects.

As an exciting, mind grabbing story it certainly works. And because the big bang story does seem to be based on factual observation and the scientific method, it seems to many people more reasonable than religious accounts of creation. This big bang theory of cosmology is, however, only the latest in a series of attempts to explain the universe in a mechanistic way, a way that sees the world — and man — solely as the products of matter working according to materialistic laws.

Scientists traditionally reject supernatural explanations of the origin of the universe, especially ones involving a Supreme Person who creates it, saying that they would contradict their scientific method. In the mechanistic world view, God, if He exists at all, is reduced to the role of a petty servant who merely winds up the clock of the universe. Thereafter He has no choice but to allow everything to happen according to physical laws. This makes these laws, in effect, more powerful than God Himself. Or else God becomes simply a formless universal energy. There is definitely not much room for a personal God, a supreme designer and controller, in the universe described by the big bang theorists. Erwin Schrodinger, the Nobel-prize-winning Austrian theoretical physicist who discovered the basic equation of quantum mechanics, states in Mind and Matter, “No personal god can form part of a world model that has only become accessible at the cost of removing everything personal from it.”1 Thus we should not think that it is by their empirical findings that scientists have eliminated God from the universe or restricted His role in it. Rather from the very start their chosen method rules out God.

The scientists’ attempt to understand the origin of the universe in purely physical terms is based on three assumptions: (1) that all phenomena can be completely explained by natural laws expressed in the language of mathematics, (2) that these physical laws apply everywhere and at all times, and (3) that the fundamental natural laws are simple.

Many people take these assumptions for granted, but they have not been proven to be facts — nor is it possible to easily prove them. They are simply part of one strategy for approaching reality. Looking at the complex phenomena that confront any observer of the universe, scientists have decided to try a reductionistic approach. They say, “Let’s try to reduce everything to measurements and try to explain them by simple, universal physical laws.” But there is no logical reason for ruling out in advance alternative strategies for comprehending the universe, strategies that might involve laws and principles of irreducible complexity. Yet many scientists, confusing their strategy for trying to understand the universe with the actual nature of the universe, rule out a priori any such alternative approaches. They insist that the universe can be completely described by simple mathematical laws. “We hope to explain the entire universe in a single, simple formula that you can wear on your T-shirt,”2 says Leon Lederman, director of the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois.

There are several reasons why the scientists feel compelled to adopt their strategy of simplification. If the underlying reality of the universe can be described by simple quantitative laws, then there is some chance that they can understand it (and manipulate it), even considering the limitations of the human mind. So they assume it can be so described and invent a myriad of theories to do this. But if the universe is infinitely complex, it would be very difficult for us to understand it with the limited powers of the human mind and senses. For example, suppose you were given a set of one million numbers and asked to describe their pattern with an equation. If the pattern were simple, you might be able to do it. But if the pattern were extremely complex, you might not even be able to guess what the equation would be. And of course the scientists’ strategy will also be unsuccessful in coping with features of the universe that cannot be described in mathematical terms at all.

Thus it is not any wonder that the great majority of scientists cling so tenaciously to their present strategy to the exclusion of all other approaches. They could well be like the man who lost his car keys in his driveway and went to look for them by the streetlight, where the light was better.

However, the scientists’ belief that the physical laws discovered in laboratory experiments on earth apply throughout all time and space is certainly open to question. For example, just because electrical fields are seen to behave a certain way in the laboratory does not insure that they also operate in the same way at vast distances and at times billions of years ago. Yet such assumptions are crucial to the scientists’ attempts to explain such things as the origin of the universe and the nature of faraway objects such as quasars. After all, we can’t really go back billions of years in time to the origin of the universe, and we have practically no firsthand evidence at all of anything beyond our own solar system.

Even some prominent scientists recognize the risks involved in extrapolating conclusions about the universe as a whole from our limited knowledge. In 1980, Kenneth E. Boulding, in his presidential address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, said: “Cosmology … is likely to be very insecure, simply because it studies a very large universe with a very small and biased sample. We have only been looking at it carefully for a very small fraction of its total time span, and we know intimately an even smaller fraction of its total space.”3 But not only are the cosmologists’ conclusions insecure — it also seems that their whole attempt to make a simple mathematical model of the universe consistent with its observable features is fraught with fundamental difficulties, which we will now describe.

The Dreaded Singularity

One of the greatest problems faced by the big bang theorists is that although they are attempting to explain the “origin of the universe,” the origin they propose is mathematically indescribable. According to the standard big bang theories, the initial condition of the universe was a point of infinitesimal circumference and infinite density and temperature. An initial condition such as this is beyond mathematical description. Nothing can be said about it. All calculations go haywire. It’s like trying to divide a number by 0 — what do you get? 1? … 5? … 5 trillion? … ??? It’s impossible to say. Technically, such a phenomenon is called a “singularity.”

Sir Bernard Lovell, professor of radio astronomy at the University of Manchester, wrote of singularities, “In the approach to a physical description of the beginning of time, we reach a barrier at this point. The problem as to whether or not this really is a fundamental barrier to a scientific description of the initial state of the universe, and the associated conceptual difficulties in the consideration of a single entity at the beginning of time, are questions of outstanding importance in modern thought.”4

As of yet, the barrier has not been surmounted by even the greatest exponents of the big bang theory. Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg laments, “Unfortunately, I cannot start the film [his colorful description of the big bang] at zero time and infinite temperature.”5 So we find that the big bang theory does not describe the origin of the universe at all, because the initial singularity is by definition indescribable.

Quite literally, therefore, the big bang theory is in trouble right from the very start. While the difficulty about the initial singularity is ignored or glossed over in popular accounts of the big bang, it is recognized as a major stumbling block in the more technical accounts by scientists attempting to deal with its actual mathematical implications. Stephen Hawking, Lucian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge University, and G.F.R. Ellis, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cape Town, in their authoritative book The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time point out, “It seems to be a good principle that the prediction of a singularity by a physical theory indicates that the theory has broken down.”6 They add, “The results we have obtained support the idea that the universe began a finite time ago. However the actual point of creation, the singularity, is outside the scope of presently known laws of physics.”7

Any explanation of the origin of the universe that begins with something physically indescribable is certainly open to question. And then there is a further difficulty. Where did the singularity come from? Here the scientists face the same difficulty as the religionists they taunt with the question, “Where did God come from?” And just as the religionist responds with the answer that God is the causeless cause of all causes, the scientists are now faced with the prospect of declaring a mathematically indescribable point of infinite density and infinitesimal size, existing before all conceptions of time and space, as the causeless cause of all causes. At this point, the hapless scientist stands convicted of the same unforgivable intellectual crime that he has always accused the saints and mystics of committing — making physically unverifiable supernatural claims. If he is to know anything at all about the origin of the universe, it would seem he would now have to consider the possibility of accepting methods of inquiry and experiment transcending the physical.

Attempted Solutions

Unwilling to face this distasteful prospect, theorists have proposed a multitude of variations on the big bang theory in an effort to sidestep the singularity problem. One approach has been to postulate that the universe did not begin with a perfect singularity. Sir Bernard Lovell states that the singularity in the big bang universe “has often been regarded as a mathematical difficulty arising from the assumption that the universe is uniform.”8 The standard models for the big bang universe have perfect mathematical symmetry, and some physicists thought this was the cause of a singularity when they worked out the mathematical answers to the equations for the big bang’s initial state at time zero. As a correction, some theorists introduced into their models irregularities similar to those of the observed universe. This, it was hoped, would give the initial state enough irregularity to prevent everything from being reduced to a single point. But this hope was dashed by Hawking and Ellis, who state that according to their calculations a big bang model with irregularities in the distribution of matter on the observed scale must still have a singularity in the beginning.

Credits: Copyright BBT

Ref.VedaBase OM 1: Big questions about the big bang

Ref.VedaBase OM 1-2: Attempted Solutions

Ref.VedaBase OM 1-1: The Dreaded Singularity

Posted in

Posted in